This is Not My Tree – A conversation about Migration

Eleven artists talking about migration, belonging, ecosystems, hierarchies, and invasive species. In conversation with curator Nina Mdivani on the event of the opening of the exhibition at NARS Foundation, Brooklyn March 26 – April 16, 2021.

Installation view, This Is Not My Tree, March 26- April 16. NARS Foundation, Brooklyn.

Works by Lia Kim Farnsworth and Omer Ben Zvi. Photo by Lia Kim Farnsworth.

Installation view, This Is Not My Tree, March 26- April 16. NARS Foundation, Brooklyn. Photo by Jon Gomez.This exhibition is a visual analysis of migration across state borders that uses as its method concepts habitually reserved for environmental studies. Notions of ecosystems, hierarchy, invasive species and natural equilibrium are used by fourteen artists in the exhibition. Artists come from the United States, Saudi Arabia, Colombia, Israel, and Georgia. Evoking complexity of relationship from one person to another, artists insist on long-term meditation in approaching these subjects, later creating critical or poetic responses. In a way this show is not looking at individuals, but rather for relations between individuals as they create societies. All of presented artists engage with the discourse of land, journeys, belonging, borders and human lives. Purpose of the exhibition is not to dehumanize the interconnectivity by using biological language and frameworks, but to show that multiplicity of perspectives is a part of the novel ecosystems, in society and in nature. Eleven participating artists are presented below as they grapple with questions about their personal stories of migration as well as larger patterns and emotional undercurrents.

Yael Azoulay, This is Not My Tree (Oconomowoc, Wisconsin), 2021, UV pigment print on Plexiglass, light box, 7x12 inches. Photo courtesy of the artist.YAEL AZOULAY, Israel

What is your personal experience with immigration/emigration?

I am an Israeli who lived in the US for 6 years. Furthermore, both my parents were born outside of Israel, and are currently living in the US. I have often wondered if the fact that they had experienced migration as children, made it easier for them to leave Israel and move to the U.S.

How did/does it inform your work?

For the past three years I have been dealing mostly with the notion of displacement and immigration. Using Eucalyptus tree as a metaphor, I am exploring the notion of what it means to be non-native. Even after I moved back to Israel last summer, I am still dealing with ideas like switching backgrounds and fitting in, as I feel it is relevant for me even in my own country.

How do you see immigration correlating with the environmental factors?

When I lived in the States I was in a constant awe of its wild forests and many shades of deep green they possess. I asked myself, if I lived the rest of my life in the U.S. will I ever start to feel like these forests are mine? That I am part of them and they are a part of me? I’m not sure what the answer is. Moving back to Israel I found that the awe for these forests is still there, but I feel like the environment here is more accessible to me, physically, but also emotionally and mentally.

What comes to your mind when you hear ‘invasive species’?

For me notions ofnon-native and invasive species connect very much to my experience with the Eucalyptus. I grew up while having this tree in my background, hanging out in its shade for more hours than I can count. When was abroad about twenty years ago, I turned on the TV and saw Eucalyptus trees. I got excited thinking that this movie was shot in Israel, only to found out what I already knew and forgotten – this is an Australian tree. This experience challenged my sense of home – something that feels like home, but it isn’t. This is of course heightened by the political history of Israel, as well as coming from a long tradition of wandering Jews.

What are the main themes you engage with in your work in the current NARS exhibition?

My work is part of a series called This is not my Tree. This work was shot in both Israel (the Eucalyptus) and Oconomowoc, Wisconsin (the background trees). The “Israeli” tree tries its best to fit in the Wisconsin landscape, but fails. The two images are printed on different layers of Plexiglass, so that no matter how hard it tries, the tree will never actually fully blend in. There are two more landscapes in which the same tree tries to fit in. This series are based on locations that were meaningful to me in my journey to feel at home in the US.

Eli Barak, A Rolling Stone, 2018, still from video, 5:00. Photo courtesy of the artist.ELI BARAK, United States

What is your personal experience with migration?

I moved to the U.S. when I turned thirty, today over a decade later I’m still conflicted whether I am an immigrant and whether I am home. In that there is a strong sentiment that longs to find home, to recreate the feeling of being at home. At the same time, I’m afraid of shedding pieces of my ethnicity, afraid of fully becoming an American.

How do you see immigration correlating with the environmental factors?

In our time immigration has become a worldwide phenomenon. Immigration crises are fueled by political turmoil ranging from refugees fleeing from war zones of the Middle East to simply people seeking water after continuing droughts in their countries.

How have the notions of hierarchy and ecosystem affected you? It could be the natural and/or social environment you grew up with or moved into.

Both of my parents migrated to Israel from Arab countries and did their best to be a worthy citizen. As part of that aspiration especially for Jews of Arab descent we needed to assimilate to blend in with the sabra (term used for Israeli-born Jews). Most of Mizrahi or Oriental Jews were considered lower class and also culturally misrepresented.

What comes to your mind when you hear ‘invasive species’?

Actually, I give a lot of “credit” to humans for disrupting the natural equilibrium. But also, what comes to mind are aquariums, cages, birds and how humans have depleted all other species to the brink of extinction just because the human race is being super self-centered.

What are the main themes you engage with in your work in the current NARS exhibition?

Rolling Stone is documentation of my performance that incorporates a desire to have a place in society. This use of metaphor follows a more historic legend that evolved from Christianity. Medieval legend of the wandering Jew reflects on the idea of being out of place and in a condition of a perpetual diaspora. I created the video/ performance “A Rolling Stone” as a tribute to my late mother. Since moving to the US I experienced an identity conflict that only got stronger with my mother’s passing, throughout her life she was my rock, she was the bridge to my ethnicity. My mental and emotional place is a key influence and motivation for this work. The feeling of misplacement and the constant longing to a physical home. I create a space for work to exist in, I claim the public space, I wonder through the streets of New York as a blind rock (I literally cannot see inside the sculpture), hoping to engage in a non-verbal dialogue. In that act I take a bait of the big apple without an official permission.

Omer Ben Zvi, Galls, 2018, glazed white earthenware clay, Installation approximately 6 x 5 feet, individual dimension vary.

Photo courtesy of the artist.OMER BEN ZVI, United States

What is your personal experience with immigration/emigration?

Three of my grandparents immigrated to Israel from other countries; and although I am a fourth-generation born in Israel, their experiences as immigrants were consistently present in their life and in mine. I remember their slight accent or use of foreign words, the stories of their family and community, their journey to Israel, and the traditional food they made. There was something about them that never became completely ‘local’. I think I always felt it and maybe even internalized some of it.

Five years ago, I moved to New York to pursue an MFA degree. It was a decision I did not take lightly but I made it freely. I had to recreate my life – almost from scratch – and it was undeniably difficult. But I remember thinking – how lucky I am that I had a choice, and how incredibly hard it must be for someone who is displaced or forced to leave their home.

How did/does migration inform your work?

When the past is not fully resolved, the present will continue to be disrupted. The motifs of identity and memory are recurrent in my work. Coming from a diverse immigrant background and growing up in a young country that tries to establish its own modern identity based on its historic roots, deeply impacts me and my work. I frequently focus on the ideas of both collective and familial memory, as well as what constitutes an archive.

How do you see immigration correlating with the environmental factors?

Just like the hunter-gatherer communities of the past, people today are moving to different places to achieve a better life for themselves and their families. If the gloomy forecasts of climate change occur, coupled with globalization and the attempts to dismantle the idea of the nation-state, we will see more migration waves. Areas will run out of drinkable freshwater and other environmental sustainability elements will be depleted. The motivation to migrate will change from ‘comfort’ to survival.

How have the notions of hierarchy and ecosystem affected you? It could be the natural and/or social environment I grew up with or moved into.

All ecosystems have balance. Whenever a new organism is being introduced, starts a weird ‘dance’ that tries to restore or maintain the balance. The organism can either die immediately, likely due to its inability to sustain itself, or it can adapt to its new environment. The environment can either contain that change or reject it. I find this balancing dance fascinating.

What comes to your mind when you hear ‘invasive species’? Irresponsibility and carelessness. We do not fully understand the damage we do with our reckless and selfish behavior.

What are the main themes you engage within your work in the current NARS exhibition? The work I am showing in the exhibition is a depiction of plant-galls; abnormal growth of plant tissue caused usually by insects. Galls act as both the habitat and food source for the gall’s maker and may also function as physical protection. My main inquiry is: Is this tissue growth an invasion? And, since the plant is not damaged drastically by the galls or killed during the process, is the process – harmful or helpful?

Delano Dunn, Far Back To Sanity, 2019, mylar, copper tape, masking tape, paper, vinyl,

woodstain, and shoe polish on wood, 48 x 35 inches. Photo courtesy of the artist.DELANO DUNN, United States

What is your personal experience with immigration/emigration?

My experience with immigration has been from a distance. My great grandfather on my father’s side was an immigrant. He often spoke of the opportunities he received in this country (U.S.), about the value of family and of community. Yes, they are general themes, but they were important to him. And he wanted to pass these beliefs onto his children and down the line. Another experience with immigration was growing up in a LA neighborhood where the ethnic dynamic shifted from a neighborhood that was predominantly African American to one that is predominantly Latino. Witnessing this change at a young age made me understand that there was beauty found in the introduction and exploration of other cultures. It instilled in me empathy and curiosity.

How did/does migration inform your work?

The idea of the Family, the dynamics of how values can affect a person, and what happens when those values are thrown to the side by others. At times my work can focus on repercussions. The introduction of a large Latino community into my neighborhood when I was growing up also affected my work. The shifting demographic reaffirmed empathy and compassion for those around me. It made me want to bring those ideas into my work.

How do you see immigration correlating with the environmental factors?

There was a huge shift in my environment as a child due to immigration. Everything around me changed. From something as simple as saying hello to a person walking down the street, to the friendships I forged as a child. It pushed me to be social. I learned new things and experienced a new culture. The food in the neighborhood changed. Restaurants closed and new ones opened. I did my best to learn a new language. It had a huge impact on the neighborhood. For many the reaction was to leave, to escape. There was a black flight. And I have compassion for that. It is very difficult to see everything you have known disappeared.

How have the notions of hierarchy and ecosystem affected you? It could be the natural and/or social environment you grew up with or moved into.

The hierarchy in the neighborhood shifted. Blacks who were the dominant voice in the community were in some ways pushed to the side in favor of the growing Latino community. The loudest voices in the room get heard as they say. Many African Americans felt an additional disenfranchisement lumped on top of the already general disenfranchisement affecting them in America. This contributed to the Black flight. It’s strange at times to me because that disenfranchisement should have been a universal theme that bonded the two groups together. But unfortunately, it did not. It caused a rift. My family stayed because we had strong roots in the community. We welcomed the new dynamic. It did not scare us. Maybe in some way we felt a connection to the idea of being an outsider coming into a new place.

What comes to your mind when you hear ‘invasive species’?

I think of people who feel that their opinion or point of view is more important than others are in fact invasive species. I think of individuals that shut down a conversation because they are unable to see the nuance in a situation. Religion comes to mind. ‘My God is better than your God’. ‘My pain is great then your pain’. That is invasive to me. An outside force doing whatever it can to push its own agenda with little to no empathy for others.

What are the main themes you engage with in your work in the current NARS exhibition?

“Far Back to Sanity” deals with the Los Angeles Riots. A time when tensions between the African American and Asian Americans, as well as the police were at their height. In the work you see an African American man who has stepped in to help an Asian American who was brutally attacked during the riots. It’s a moment of empathy. A moment in which race and ethnicity is transcended in favor of unity and compassion. It’s a hard image to look at. But there is hope in it. That people can move beyond their differences and help and support one another. I like to think that gets across in the work.

Jan Dickey, The darkened house and the gate, 2020, milk paint, egg, rabbit skin glue, cellulose glue, oil on wood & canvas 80 x 38 inches. Photo courtesy of the artist.JAN DICKEY, United States

What is your personal experience with immigration/emigration?

I have been a citizen of the United States of America since I was born in Bad Kreuznach, Germany in 1987. My father was what they call a “military brat,” his own father having worked for the Department of Defense in Japan, the Philippines, Taiwan, and finally Germany. My mother is the child of Latvian immigrants who emigrated from their home country during WWII when the Soviets invaded. Her parents lived in a Nazi refugee camp until they were sponsored by a Christian church in Ohio to immigrate. I lived with my family in Bad Kreuznach until I turned 9, when we relocated to the state of Delaware. My family relocated to Kentucky when I was 18, and I stayed in Delaware to go to college. From there I moved to California, then New York, then North Carolina, then Hawaii, and finally back to New York. I don’t identify very strongly with one specific place in the world, but have found I am most at home in sub tropic climate zones and I generally act like an American.

How did/does it inform your work?

My family and my own history of movement has shaped my perception of nation states and the ecological regions of Earth they claim as “territory.” Specifically, I see nation states––or any kind of human-made organizational body––as being an abstract enclosure that is inevitably temporary. The precariousness of solid forms––both physical and imaginary––is at the heart of my art practice.

How do you see immigration correlating with the environmental factors?

A group of people can get together and call an area of land their state or their country until they no longer have the power to do that. I am really fascinated by the process of human beings trying to stake out a claim on ecological spaces in this way. There is deep psychological need we are trying to satisfy when we do this, that feels tragic and poet. Sometimes such territorial borders follow along some sort of ecological border––like a big river, an ocean, or a mountain range. Other times a border is just arbitrary lines. Look at Colorado––its just a rectangle drawn around a really ecologically diverse space! But human-made borders can never truly follow a natural line, because nothing like that actually exists in physical reality. The planet is composed of forms and forces that interpenetrate one another in incredibly complex ways. Even if there is a big mountain in the way, you get some level of ecological interaction between both sides of the mountain. Edges are just in our minds, but we love them so much. I love them! I’m a painter. Painting is all about edges.

How have the notions of hierarchy and ecosystem affected you? It could be the natural and/or social environment you grew up with or moved into.

I grew up in a few different places that were all in sub-tropical climate zones. I feel a connection to sub tropic ecology whether it is in Germany, the United States, or Japan. It feels familiar to me. I lived in Honolulu, HI, a tropical climate zone, for five years and it never felt familiar to me. I think that the climate zone I grew up in defined my personal sense of what is familiar or unfamiliar. When I think of the title for this show, “This is not my tree,” I think of the feeling that I had walking mountain ridges and swimming above the coral on Oahu. It was amazing and beautiful, but it never became familiar. Maybe it would with more time, but now I’m back in the Northeast US so I may never know. As far as hierarchy, I always associate hierarchy with human beings. I think hierarchical organization is something that evolved within humans as species––either genetically or culturally (hopefully just culturally). Hierarchical organization has been effective at accomplishing a lot of things, but that’s not to say another form of social organization wouldn’t have been as effective or can’t be in the future. In fact I think that if we stick with hierarchical organization, it will be our undoing as a species. Hierarchy is nasty business. It has facilitated a lotof awful things that have gone on between humans, between humans and animals, and between humans and the rest of the planet in general. I think this form of organization may ultimately lead to a huge contraction of the world population, as more and more parts of the planet become unlivable. This is already happening and the evidence for it there to see in the growing number of climate refugees, but I’d also like to thank Octavia Butler’s novel Dawn for putting that idea in my head: hierarchy as a fatal flaw in our evolution that will un-do us again and again (if given the chance). I suspect that more often than not the idea of hierarchies existing in the nonhuman world is largely just us anthropomorphizing. But I can also entertain the idea that hierarchy is a real tendency that emerges as a survival tool (i.e. not just specific to us) like having eyes or legs. Eyes and legs are survival tendencies, and maybe hierarchy is too. But regardless of whether it is a specifically cultural ideology or an emergent natural tendency, I don’t think hierarchical organization is either predetermined or essential to life. I think we can and need to evolve away from that from hierarchies toward something more equitable and caring.

What comes to your mind when you hear ‘invasive species’?

I think of invasive species as something that has the potential to radically change an ecological system, within a particular area, once it is introduced. This can look like destruction, but also the creation of something is new––a new kind of ecological system that requires new subsistence strategies. Let’s imagine that Kudzu is introduced to an island and then in 100 years the only plant on that island is Kudzu. I’m using Kudzu, because Margaret Atwood used it like this in Oryx and Crake (all my opinions on things are shaped by sci-fi authors). I don’t think there is anything intrinsically wrong, from a purely ecological standpoint, with an island where the only plant is Kudzu. However, every animal that can’t eat Kudzu is going to die unless they are genetically modified to eat it or you start bringing in food from other places. You have to ask yourself, what kind island do you want to live on? Do you want to live on an island where everything has to either: 1. drastically change in order for it to survive or, 2. become dependent on exterior ecosystems in order to survive? I think situation 1 and 2 are the dilemmas that many parts of the world are in right now, because systems for surviving on what is mainly produced locally have been dismantled by the merciless coupling of capitalism and imperialism. As a result, our existence on the specific areas of land––the places where we each individually live––has become increasingly precarious.

Michal Geva, Untitled, 2021, acrylic, oil pastels and collage on canvas, 55x43 inches. Photo courtesy of the artist.MICHAL GEVA, Israel

What is your personal experience with immigration/emigration?

I was born in an Israeli kibbutz into a family of artists. When I was five, I moved with my family to New York for several years. In my family, Art has always been a way of life, always part of the reason and the attempt to move, to migrate, and to find a new ground. In the summer of 2014, I moved once again to the U.S, and started the MFA program at the School of Visual Arts in the fall of that year. I stayed in New York for 6 years, and moved back to Israel 4 months ago, after the Covid19 pandemic changed the city and our lives, and for me became the catalyst for emigrating back home, to Israel.

How did/does it inform your work?

In my work, I explore an infringement of natural and manufactured structures on unstable ground or soil asa metaphor for belonging, as well as for anxiety and loss. Distorted views evoke the universal experienceof remote landscapes, as nostalgic and wounded echoes of an immanent entropy as they expose thefragility of architecture, nature, Ideology, and human nature.

I grew up in Israel, a country that has experienced extreme ideological shifts throughout its short history. A change has been constant from the socialist-utopian attempts of the years preceding and following the establishment of Israel to a time when a country is being dominated by right wing neo-capitalist ideology and is situated in the state of a constant war. Landscapes in my paintings serve as a representation of the broken Israeli dream and the breakdown that occurred in its society as they highlight the gaps, the clashing points and the sinkholes. At the same time they mirror a much broader existential, psychological and universal aspects of entropy, collapse and disintegration. My works integrate together a basic desire for stability, belonging and Gestalt, alongside with an anxiety brought about by a deep-seated sense of impermanence and lack of stability.

What comes to your mind when you hear ‘invasive species’?

In a city like New York, “local” as a term holds a continuous state of both ephemerality and totality. The city is always just a stop on the way to the next destination, while time goes by and temporality becomes the most permanent thing. Everyone is a foreigner there, invasive species coming from different places and trying to put their roots down into a new ground. My experience with this attempt raised many questions and doubts about the possibility of truly integrating with this new environment: Can invasive species, such as ourselves, really become a natural part of our new habitat and landscape? In a similar way to the landscapes in my paintings, my experience with immigrating to New York was always accompanied, both physically and mentally, by these notions of displacement, transience, alienation, and being in a place where I am an outsider and an insider at the same time.

Lia Kim Farnsworth, Northeastern Regional Ecology Center, 2017, digital photo print, 70 x47 inches.

Photo courtesy of the artist.LIA KIM FARNSWORTH, United States

What is your personal experience with immigration/emigration?

My mom immigrated to the United States from South Korea. I was born in the United States, but lived in Korea as a child. I always felt that while I technically belonged to two different places, both by birthright and by my language and culture, in some ways I didn’t fully belong to either place.

How did/does it inform your work?

I don’t necessarily think of my experience with immigration as having much of an impact on my body of work as a whole, but I can see some threads of its impact in a few of my pieces. In my work Northeastern Regional Ecology Center, for example, I played with the idea that invasive plant species or weeds might be something we would revere and cherish in a future without what we currently think of as nature.

How do you see immigration correlating with the environmental factors?

Whenever I think of the future effects of climate change, I think of mass migration. I think of the displacement of millions or even billions of people as their environment becomes incompatible to human life. I think that displacement is such an impossible concept to fully envision or understand. Our culture is so embedded in our environment – what we eat, how we interact with the land, how we interact with each other, our language, how we conceptualize ourselves. I think that mass displacement out of necessity will also correlate with a loss of identity and loss of self.

How have the notions of hierarchy and ecosystem affected you?

It could be the natural and/or social environment you grew up with or moved into. In some of my past works, I’ve considered the effect of class and privilege on our access to nature. I’m interested in how we might begin to commodify a specific, limited version of the natural world that we conceptualize as nature, and how that commodification might render that version of nature as more valuable or precious than the natural life around us. There might be a hierarchy within the classification of plant and animal species, and then issues of who has access to those plant and animal species.

What comes to your mind when you hear ‘invasive species’?

It’s hard for me to fully understand how much climate change is going to alter what I currently perceive as nature, including the plant and animal species that are part of my mostly subconscious conceptualization of nature. With vast shifts in our climate and habitable environments, I’m interested in which plant and animal species begin to thrive in new environments, and which can no longer survive. I feel like there is a conservative tendency to hold onto what has historically been true – including which people, plants, and animals might have historically habited a space. I wonder what happens when enormous shifts beyond our control completely change the makeup of that space. Are the species that now thrive in that space truly invasive, or does it all come down to survival in the end?

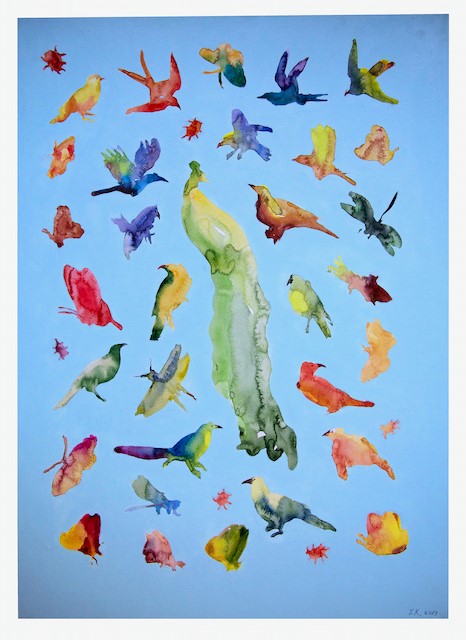

Tamara Kvesitadze, Sky, 2019, watercolor on wood board, 28 x 20 inches. Photo courtesy of the artist.TAMARA KVESITADZE, Georgia

What is your personal experience with immigration/emigration?

In the 1990s when there was a civil war in my home country, Georgia, I had to travel to New York, where I stayed for five years. Although I visited home throughout this time, I was fully enveloped in New York life and probably these were the best years. As it was the beginning of a new life for me, getting to learn and internalizing new, different art and culture on a deeper and more meaningful level. I was absolutely delighted although as everyone else I have encountered barriers specific to immigrants. Language barriers, establishing relationships with galleries were all difficult, also because there was a lack of information in Georgia about the way the art world operates. I was 28 then and decided to stay in the United States. As I had two children at that point, I thought that if I immigrated, I will have less time to devote to art. But in the end based on some personal circumstances I moved back to Georgia. Even today I do not know if this decision was right or wrong.

How did/does it inform your work?

New York period has deeply affected me and naturally, my art. Impact of this new urban environment was revealing of some impulses hidden before. New works emerged, quite different from old ones and this transformation has happened naturally. I would say New York has started a new chapter in my artistic approach.

How do you see immigration correlating with the environmental factors?

Migration can be caused by political or natural causes. Today in Georgia there is a plan for building a new massive hydroelectric power plant and this construction is associated with many issues, including flooding of many villages and displacement of families who have lived there for generations. This type of construction is sometimes useful and necessary for the state however in case with Georgia it could be disastrous. Rapid modernization of the last decades has already affected the country very negatively as no one is really concerned with the health of the endemic ecosystem.

How have the notions of hierarchy and ecosystem affected you?

I have worked and lived continuously in different countries. There is a saying in Georgia, ‘wear a hat of the place that you are in.’ I think there is a great wisdom in this saying that also alludes to changes that take place in a person when she leaves. Significant changes are often associated with difficulties, but overall, they always bring positive developments. In reality they always serve self-preservation of an individual. Most importantly is for the person not to lose her identity, be stronger than an environment that surrounds her.

What comes to your mind when you hear ‘invasive species’?

If there is something that is bound to happen, it’s better to accept it in order to survive.

What are the main themes you engage with in your work in the current NARS exhibition?

This watercolor, a small work compared to sculptures and installations I usually work with, is about a flight. It is about a utopia; we all call freedom.

Netta Laufer, 25Ft, 2016, still from video, 25:00. Photo courtesy of the artist.NETTA LAUFER, Israel

What is your personal experience with immigration/emigration?

I’ve personally experienced immigration/emigration from several perspectives. Firstly, as an Israeli and a Jew, I am well aware of my country’s history and heritage which was built on immigration. Personally, I am a third generation of immigrants. My grandparents came from Europe either before or as a result of World War II. Secondly, five years ago I spent several years in New York for my master’s studies at the School of Visual Arts. As a student in a foreign land, I personally experienced the cultural differences and especially the difficulties arising from the language barrier.

How did/does it inform your work?

My personal experiences with regards to immigration/emigration do not affect my work directly. However, as an Israeli, my work, which deals with land and nature, naturally focuses on geographical territories that are part of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and as a result, raises questions in regards to belonging to one’s land.

How do you see immigration correlating with the environmental factors?

My work deals with the separation wall between Israel and Palestine, and its significant impact on nature. It changed the balance of the ecological system by creating a division between animal groups and altering their paths and habitats.

How have the notions of hierarchy and ecosystem affected you? In the last 7-8 years, my main interest has been the power dynamics between humans and animals through political power systems. I’m always looking to investigate and observe different aspects of this relationship.

What comes to your mind when you hear ‘invasive species’?

As animals adjust and change their habitats as a result of either man-made or natural ecological changes, we have taken the authority upon us, to determine and define some of them as ‘invasive species’. Using the term “Invasive” automatically suggests that the animal has forcibly invaded one’s territory, and depicts it as an “enemy” or a “problem” that needs to be taken care of. The most common solution to eliminate this “problem” – killing them.

What are the main themes you engage with in your work in the current NARS exhibition?

My works deal with the tremendous postcolonial outcomes of human-made artificial borders on the fauna and flora. I research and carefully distinguish between the variety of ways in which nature and wilderness have been altered and domesticated throughout the Anthropocene. I find in the intensification of domestication an aggressive political power system that reproduces new forms of oppression.

Pedro Mesa, ¡Cabrones, qué viva el partido Liberal! (Bastards! Long live the Liberal Party!), 2018, acrylic on wood, 59 x 20 x 11 inches. Photo courtesy of the artist.PEDRO MESA, Colombia/United States

What is your personal experience with immigration/emigration?

As a temporary immigrant, experience of locality through anxiety, and transversal to that locality, the abbreviation of identities [with]in the space of predetermined categories, [cosmopolitan/international/multiracial] forms and grids [digital/physical/cultural] that chart me through language, location, and temporality. What your body is in its present location. Grids and latticework that represent me in oppositional terms that operate in time; Grids are our identities, our phones, our dormitories, neighborhoods and frontiers. The metaphorical [and real] enclosures and commons [wildernesses]; our rooms’ literal walls and our borders. The characteristic enclosures and corridors of our present and local identity. My body corresponds to a position in that grid. For all bureaucratic, migratory, social, racial, psychological, and sexual purposes, my body occupies a position/location/site on a grid defined by the layering of terms from oppositional categories. And yet, the reality is that I come from Colombia: the best and worst friend of the USA. Their back door to their backyard –but there’s a glowing EXIT ONLY neon sign above it. One-way traffic most of the time.

How did/does it inform your work?

As an artist, immigration and emigration of ideas that accompany the real, physical bodies and their cultural residues. For instance, the Colombian artistic Modernism, –a translation of German Romanticism (subsequently a form of European or continental romanticism)– simultaneously aided foundational agendas during the independence and consolidation of the country-nations of South America. A romantic modernism that is still establishing ideas of national identity, and desires to incorporate the communities not yet ‘consolidated’ or recognized within that ongoing, ever founding agenda. Processes of modernization and economic aperture that grew on the soil of colonial relations between Colombia and Spain and fertilized for the Colombian-USA relations [Am I a type of translator? Anxiety of influence]. Migration to centers of cultural and economic production like New York –participation of a ‘central’ amalgamation of culture[s]; the belief that this will determine my cultural production and its reception; an undesired place to be, but apt for breaking categories.

In my work, I’ve used abstractions of Colombian colonial architecture and linguistic features of Spanish and English as metaphors that discuss the movement between cultures. My work consists of texts, sculptures, videos, and images examining post-colonial locality as an abstracted site: devices that inquire colonialism, power, and race. The lattices of Colombian Colonial architecture are my perspective for observing the world. The porosity of the lattice serves me as a parting concept that permits an interplay of movements. These movements can be thought of in terms of lattices of Arabic, Mozarabic, and Latin-American architectures: air-flows from insides and outsides, the differences in brightness –or luminosities–, but most importantly, the possibility to gaze out[side], while being occluded/masked/observed/revealed by said movements [and pores]. This lattice as protection and revelation is remarkably ambiguous for the migrant subject. The lattice is my device to observe and be observed, a maneuver that simultaneously occludes and reveals private affectivities and ventilates sociopolitical anxieties and positionalities. The argument behind a category is the possibility to break it; we know we can achieve this by movement –a movement through avenues in a grid, as if ventilated by a lattice, but always movement, at least.

How have the notions of hierarchy and ecosystem affected you? It could be the natural and/or social environment you grew up with or moved into.

Benign forms of migration and multiculturalism have radically different avenues of movement from more hostile migration through distress, but both drift towards assimilation [a sense of belonging]. Assimilation, in turn, has a power structure [hierarchy] that leans towards the dominant culture, of course. Nevertheless, from point zero, the construct of the inside is defined through the outside –the outside changes the inside. Cosmopolitan migration versus forced migration: the repurposing of traditions and localities for survival and the simultaneous incorporation, or assimilation of local culture and customs/costumes. Consider second-generation immigrants in the United States of America, many of whom do not speak but understand the language of their family’s country. Consider the challenging movements that traditions and customs must enact from generation to generation. This issue, I believe, is quite profound and needs to be thoroughly addressed by our ensuing generations.

What comes to your mind when you hear ‘invasive species’?

Humans. Burnings in the Amazon. Mining in the Andes. Citizens from the First World touring the third and leaving cheeseburgers and sun-lotion all over the oceans; construction of bypass roads in the middle of deserts. Bulldozing forest lands and races, fragmenting habitats and natural environments, dispersing of wildlife and replacing it with ‘population’. Not all places on this Earth are meant for us.

I seek to simultaneously de-nativize myself [I drift towards/shift towards/float towards, as in by sail,] by relativizing myself. Our digital technology permits the revelation of the self [the body/of the body] through identity fragmentation across culture[s]. The kaleidoscopic fragmentation of the body, voice and position within that grid is achieved (albeit virtually, digitally) by the porous movement across and through this sets of lattices. Like us, they are made of holes that compose a whole. [W]holes allowed for movement. Holes that denote where the limits of experience, the limits of identity politics can expand towards. This lattice/grid creates transparent subjects, racialized subjects, total subjects. Subjects full of holes.

Mark Tribe, Black Brook, Balsam Lake Mountain Wild Forest, Ulster County, New York, October 2, 2016, 2021, acrylic and ink on wood panel with digitally milled walnut frame 18 x 24" (panel), 25.5 x 31” (frame). Photo courtesy of the artist.MARK TRIBE, United States

What is your personal experience with immigration/emigration?

I was born in San Francisco, California, but immigration is a big part of my family story: my father came here from Shanghai in 1945, as did my paternal grandparents; my mother’s mother, and her father’s parents, immigrated from Germany. But going back a little further, they came from different parts of Germany, from Croatia and from Belarus.

How did/does it inform your work?

I made work about my family history when I was in grad school. Since then, the immigration experiences of my elders have informed my work and my life in more indirect ways. It influenced my decision to move to Berlin in 1995, and also my decision to return to the United States a year later, after concluding that I did not want to live the life of an expatriate, and that I did not want to settle in a country that was so unwelcoming to foreigners. I lived in a predominantly Turkish neighborhood, and took German classes at a language school that catered mostly to “guest workers.” I learned that one could be born in Germany to Turkish parents and still not be considered German, or granted German citizenship.

So, I moved to New York City, partly because it is a mecca for artists, but mostly because it is the most welcoming place I’ve ever been. I read recently that it takes ten years to become a New Yorker. I disagree. I think it can take as little as ten seconds. The moment you arrive with the intention to stay, you’re a New Yorker. The government may not recognize your status, but the city will take you in.

Like many Americans, I’m ethnically remixed. We get to invent ourselves, and to find our own communities of choice, but we’re also deracinated–cut off from ancestral languages, traditions, ethnicities and homelands–and remixed. I do regret this disconnection from heritage, and admit to feeling a need to put down roots and create a sense of belonging for myself and my children, but recognize that to do so here, on the ancestral lands of Indigenous people who were killed, pushed out, cheated and betrayed by other European immigrants who came before my forebears arrived here, requires a delicate negotiation. I think a lot about what it means to not be Indigenous, and what it means to be descended from immigrants, as opposed to colonists or settlers. I also think about belonging and community. I was born in 1966 and it is now 2021. So much has changed in the world over this half-century, and things are moving and changing at a quickening pace, but I am part of a generation, we have a place in history, and we have a responsibility to address the mistakes of the generations that came before us, in terms of human and animal suffering, social injustice and ecological disruption. If these mistakes have a common root, it might be alienation: from one another and from the “natural world.” We need to reimagine ourselves as natural, as inextricably enmeshed. We need to recognize our interdependence, not only with one another but also with landscapes and waters and the sky. We need to transition from a relation of extraction to one of reciprocation and regeneration. But who am I, a city kid and backcountry traveler whose forebears came here from Asia and Europe, to put down roots on land that was stolen from people who were native to it? What are the ethics of belonging for latter day settlers? Can interdependence and interconnection between human communities and the places we inhabit be relearned? How can I, an artist and educator, be part of a just transition to a more sustainable way of being in the world?

All of these questions form and inform my artistic practice, which for the past several years has been focused on landscape, and the ways in which landscape pictures reveal how people think and feel about the “natural world” and their relationships with it.

How do you see immigration correlating with the environmental factors?

Homo sapiens is a migratory species, and the story of our rise to global dominance has become the story of every ecosystem on our amazing planet. I think about how the effects of climate change and related environmental hazards will probably make much of the planet uninhabitable, which will eventually lead to a century or more of migration on unprecedented scales–a period of tremendous instability, change, and, if I can allow myself to be optimistic, opportunity. I like the ways Kim Stanley Robinson imagines these challenges and opportunities in his 2020 novel, The Ministry for the Future.

How have the notions of hierarchy and ecosystem affected you? It could be the natural and/or social environment you grew up with or moved into.

I think I addressed this, more-or-less, above.

What comes to your mind when you hear ‘invasive species’?

Invasive species is a term we use to describe non-human flora and fauna that arrive in a novel ecosystem, usually having been brought there intentionally or inadvertently by humans, outcompete and displace species that evolved there, and spread quickly, often leading to disruptive knock-on effects.